Executive Summary:

- Cisco Talos identified three zero days in two Cisco firewall products as part of an investigation into a larger threat actor campaign called “ArcaneDoor” that targeted government-owned perimeter network devices globally, with exploitation going back to January 2024

- The zero day vulnerabilities identified are tracked as CVE-2024-20353, CVE-2024-20359, and CVE-2024-20358 – of these, only CVE-2024-20353 and CVE-2024-20359 were exploited in the ArcaneDoor campaign

- While the initial access vector leveraged in this campaign is still unknown, Cisco has released software updates & has provided steps for customers to check the integrity of their Cisco Firewall devices in their event response advisory

- When we investigated the actor-controlled IPs provided by Talos in Censys data and cross-referenced the with other certificate indicators, we discovered compelling data suggesting the potential involvement of an actor based in China, including links to multiple major Chinese networks and the presence of Chinese-developed anti-censorship software. It’s tough to draw definitive conclusions at this stage.

As the investigation into ArcaneDoor continues, further data about the victims of these attacks are expected to emerge. In the interim, please consult our Rapid Response advisory for comprehensive insights into the scale of exposed Cisco ASA devices and guidance on remediation.

Understanding the ArcaneDoor Campaign

On April 24, Cisco Talos released a report shedding light on a campaign by a previously unknown state-sponsored threat actor tracked as “UAT4356”. The campaign, dubbed “ArcaneDoor,” targeted government-owned perimeter network devices from various vendors as part of a global effort.

Talos’ investigation found that actor infrastructure was established between November and December 2023, with initial activity first detected in early January 2024. While the initial access vector used in this campaign remains unknown, Talos uncovered three zero-day vulnerabilities affecting Cisco Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA) and Cisco Firepower Threat Defense (FTD) software that were exploited as part of the attack chain: CVE-2024-20353, CVE-2024-20359, and CVE-2024-20358.

Analyzing UAT4356’s Threat Actor Infrastructure

In their excellent investigation into ArcaneDoor in collaboration with other organizations, Talos shared some interesting indicators within the attacker infrastructure leveraged by UAT4356 in this campaign.

Examining Associated Certificate Indicators:

UAT4356 Certificate and Software Indicators (Source)

Talos identified a specific pattern in both the issuer and subject names of the SSL certificates:

Certificate Pattern:

:issuer = O=ocserv,CN=ocserv VPN

:selfsigned = true

:serial = 0000000000000000000000000000000000000002

:subject = O=ocserv,CN=ocserv VPN

:version = v3

“Ocserv” is associated with OpenConnect VPN Server, an open-source VPN client commonly used to connect to VPNs like Cisco ASA. It’s plausible that OpenConnect was used by the threat actor to initially connect to the targeted network devices and carry out this exploit chain.

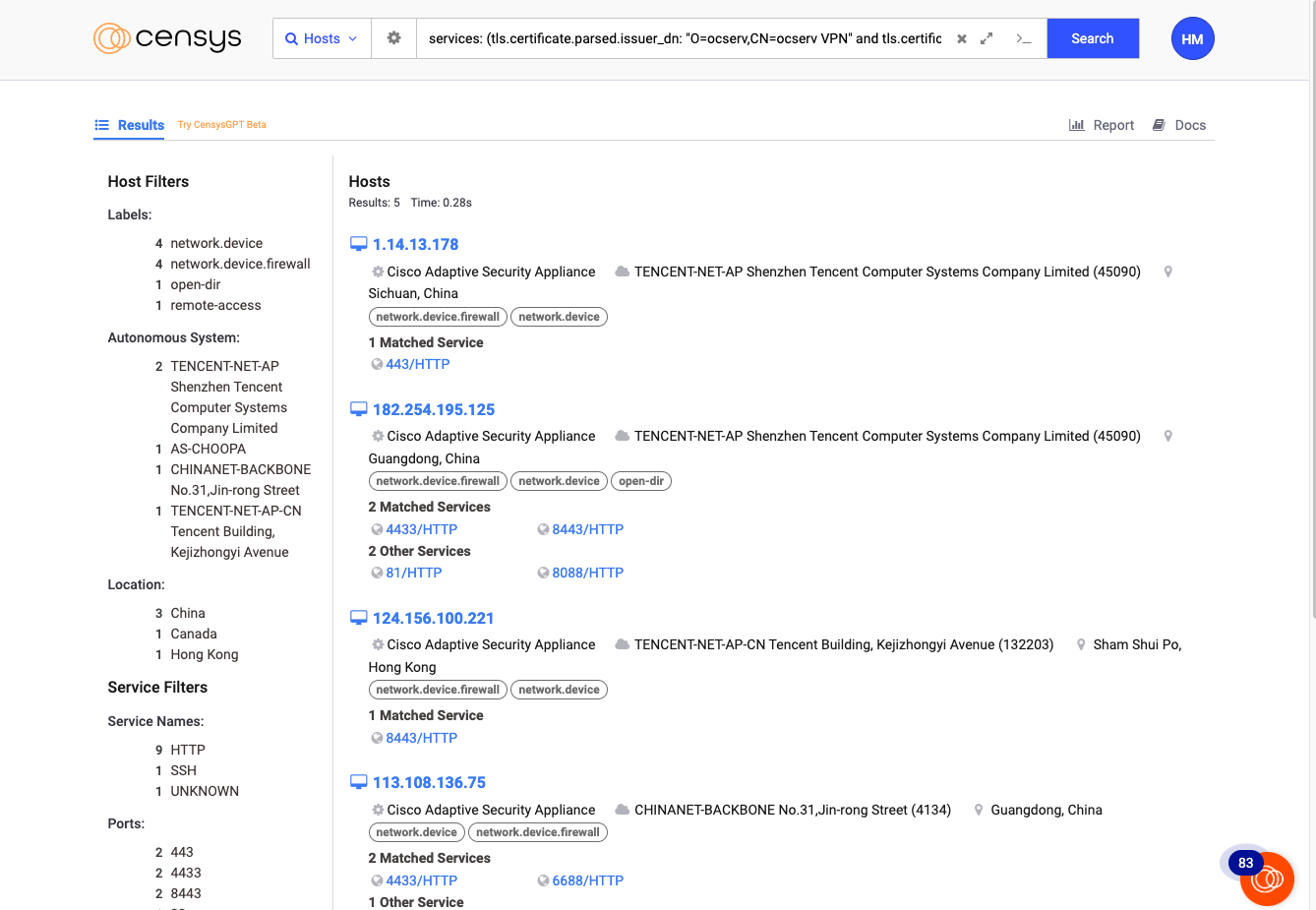

As of April 29, 2024, only 5 hosts were online presenting this certificate in Censys:

services: (tls.certificate.parsed.issuer_dn: “O=ocserv,CN=ocserv VPN” and tls.certificate.parsed.subject_dn: “O=ocserv,CN=ocserv VPN”)

Hosts presenting certificates associated with “ocserv” in Censys on April 29, 2024

The fact that there are so few hosts presenting this certificate could imply various things, but nonetheless, it’s significant. When a Censys pivot yields only a handful of results, each host holds greater significance — it means you’ve stumbled upon something distinctive in an investigation.

From this screenshot, you’ll notice that some of these hosts also appeared to be running ASA software or operating systems themselves, which aligns with observations from Talos. These are the unique CPE identifiers associated with ASA among these hosts:

cpe:2.3:h:cisco:adaptive_security_appliance:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*

cpe:2.3:o:cisco:adaptive_security_appliance_software:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*

We determined that these hosts were running ASA based on various indicators, including the presence of a Set-Cookie HTTP response header containing the string webvpncontext, a characteristic associated with ASA.

This raises the question: why do these hosts seem to be running Cisco ASA, one of the software products they were attempting to exploit? Is it somehow involved in the methods used to carry out the exploit, or is this an attempt to obfuscate their infrastructure?

Another notable clue here is the distribution of these hosts across different autonomous systems.

Networks Hosting IPs Displaying “ocserv” Certificate Indicators

| Autonomous System |

Host Count |

| TENCENT-NET-AP Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Company Limited (45090) |

2 |

| AS-CHOOPA (20473) |

1 |

| CHINANET-BACKBONE No.31,Jin-rong Street (4134) |

1 |

| TENCENT-NET-AP-CN Tencent Building, Kejizhongyi Avenue (132203) |

1 |

Four out of the five hosts are based in China. “TENCENT-NET-AP” is associated with Tencent, a Chinese multinational conglomerate headquartered in Shenzhen, while “CHINANET-BACKBONE” is run by ChinaNet, a major Chinese telecommunications company. Networks like Tencent and ChinaNet have extensive reach and resources, so they would make sense as an infrastructure choice for a sophisticated global operation like this one.

Investigating Actor-Controlled IPs:

Let’s now take a look at the list of 22 potentially actor-controlled IPs provided by Talos and plug them into Censys. Analyzing attacker infrastructure proves more advantageous compared to shared infrastructure, since it’s easier to isolate distinctive characteristics specific to the threat actor’s behavior.

As of Monday, April 29, 2024, 11 of the 22 hosts originally provided by Talos remained online in Censys scans, indicating ongoing activity within the identified infrastructure.

Let’s first look at what networks these hosts are concentrated in:

- GHOST: A Luxembourg-based cloud services provider associated with G-Core Labs S.A.

- AS-CHOOPA: A network known for high-performance network services, also known as Vultr

- ACCELERATED-IT: Provider of accelerated or high-speed internet.

- AKAMAI-LINODE: Akamai’s cloud computing infrastructure.

- ASNET: A generic-named entity, seemingly owned by “Baxet Group Inc.”

- LIMESTONENETWORKS: A hosting provider based in Dallas, Texas.

- STARK-INDUSTRIES: A Russian autonomous system believed to operate as a bulletproof hosting provider

- TSRDC-AS-AP Truxgo S. R.L. de C.V: A telecom giant based in Mexico.

When we generate a report on the issuer common names on the certificates of these hosts, there are some interesting results:

While many of these certificates appear familiar, there are a few that initially look less recognizable.

First up: WIN-16HD0VMNND5. After some digging, this looks like it may be an auto-generated RDP cert – corroborated by the fact that when we pivot to look for hosts with similar certificates in Censys (services.tls.certificates.leaf_data.subject_dn:”CN=WIN-*”), they are predominantly on RDP services.

lke155316-227342-104695750000-ca@1707338035: This looks machine-generated, and matches a pattern observed in Akamai LINODE host certificates (services.tls.certificates.leaf_data.subject_dn:”CN=lke*”).

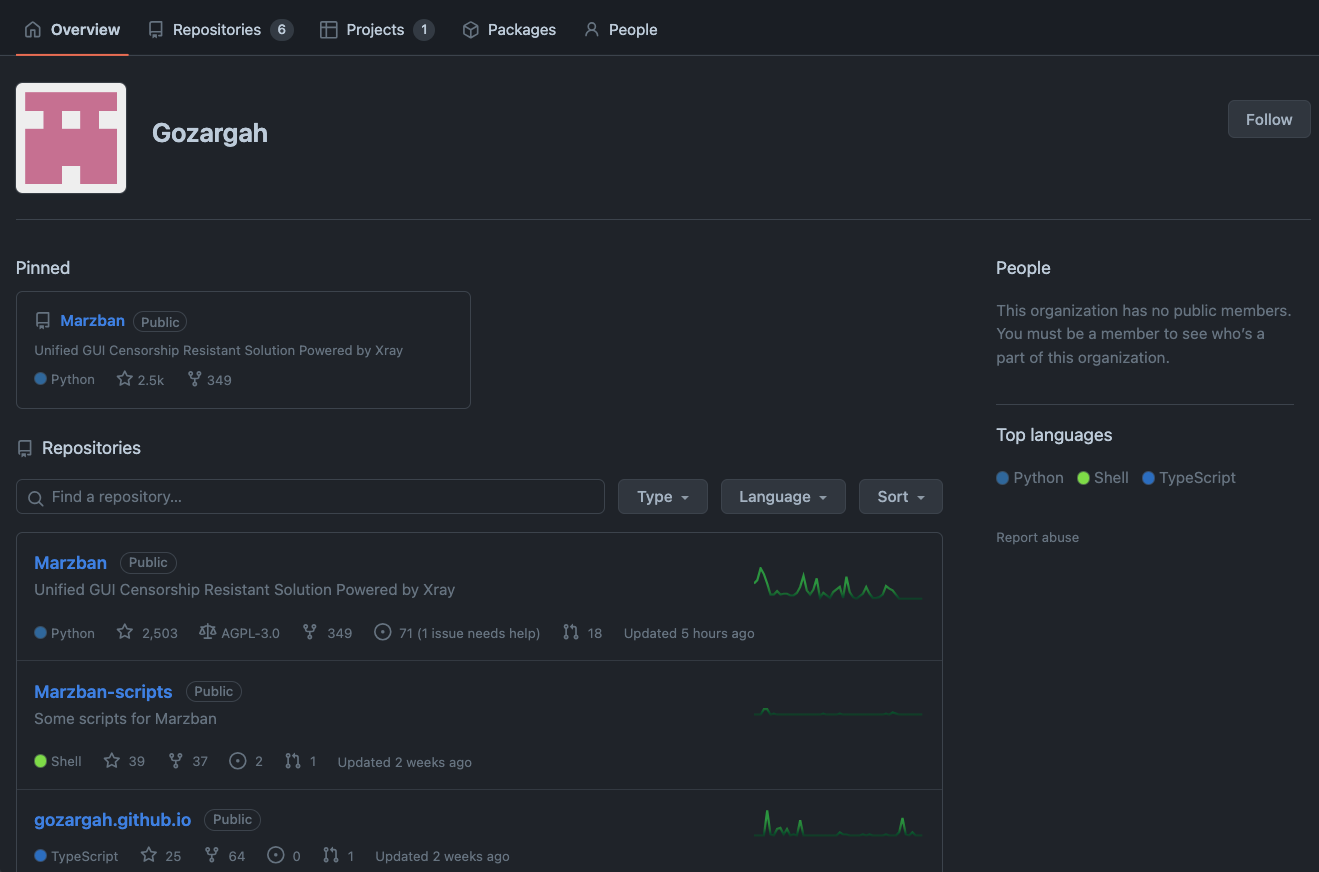

Among these, one certificate common name stands out as particularly unusual: Gozargah. Initially, this term wasn’t familiar to us.

What’s more, the two services presenting it are both on this host: 212.193.2[.]48 based in a network called ASNET, and both show up as “UNKNOWN” services in our data on TCP ports 3630 and 3631, meaning they did not fit any protocol specification we’re aware of.

Searching “Gozargah” in a web search engine takes us to this GitHub organization: https://github.com/Gozargah.

Their pinned repo is called “Marzban” (https://github.com/Gozargah/Marzban), described as “Unified GUI Censorship Resistant Solution Powered by Xray”.

What’s “Xray”?

It’s this open source project: https://github.com/XTLS/Xray-core that seems to have been developed by a community called “Project X” that’s been around since 2020: https://xtls.github.io/. Its description reads: “Xray, Penetrates Everything. Also the best v2ray-core, with XTLS support. Fully compatible configuration.”

Most of Project X’s GitHub page is written in Chinese.

XTLS, or Extended Transport Layer Security, is an extension of TLS 1.3 that uses some more advanced cryptographic techniques, obfuscates its protocol signature (making it harder to identify) and allows concealed VPN endpoint access. It makes sense that it’s being used in anti-censorship tools, since it’s most often used for bypassing firewalls. Given that it was developed by Chinese developers, it’s ostensible that it was created for the purpose of bypassing The Great Firewall, or the national firewall operated by the Chinese government.

When we pivot to look at other hosts with this certificate common name “Gozargah”, there are around 4,800 Censys-visible IPs presenting that cert (services.tls.certificates.leaf_data.issuer.common_name=”Gozargah”). Interestingly, ports 3630 and 3631 do not make the top 20 common ports list – it seems like TCP 62050 and 62051 are more popular for this service. There are only 2 other hosts with that certificate common name that have the same ports 3630 and 3631 open.

This is interesting, but is even more interesting when we go back and look at one of the hosts presenting a certificate with an “ocserv” issuer_dn flagged as an indicator by Talos: https://search.censys.io/hosts/54.179.113.92.

On TCP port 8888, this host is running some HTTP service with an HTML title reading: “Trojan Panel”

This appears to be related to this GitHub project called “trojanpanel” , which also has a website mostly written in Chinese:

It describes itself as a “multi-user web management panel supporting Xray/Trojan-Go/Hysteria/NaiveProxy.”

That makes for two mentions of this “Xray” tool linked with services running on this infrastructure.

Let’s summarize the evidence we’ve gathered so far: by cross-referencing the actor-controlled IPs and other certificate indicators identified by Talos with Censys data, we’ve discovered that (a) some of these hosts were running services associated with anti-censorship software likely intended to circumvent The Great Firewall, and (b) a significant number of these hosts are based in prominent Chinese networks.

What Does This All Mean?

Our strongest clues as to who is potentially behind this campaign come from analyzing the actor-controlled IPs in Censys, as well as pivoting off of other hosts that present the certificate indicators flagged by Talos.

The results of this preliminary investigation show a few indications that this may be the work of an actor based in China. We may see continued activity and/or changes in these hosts in our data over the coming days.

Determining whether cyber attacks are state-sponsored demands a comprehensive approach. While analyzing the networks hosting threat actor infrastructure is a piece of the puzzle, there are other factors to consider like attack methods, victims, and geopolitical context. The murky nature of this threat actor’s identity, combined with the fact that the initial access vector leveraged in this campaign is still unknown, are a cause for continued monitoring of the situation.

It’s likely that this investigation will continue to unfold as we get more details about the targets of these attacks. In the meantime, please refer to our Rapid Response advisory for more details on the scope of exposed Cisco ASA devices and remediation guidance.