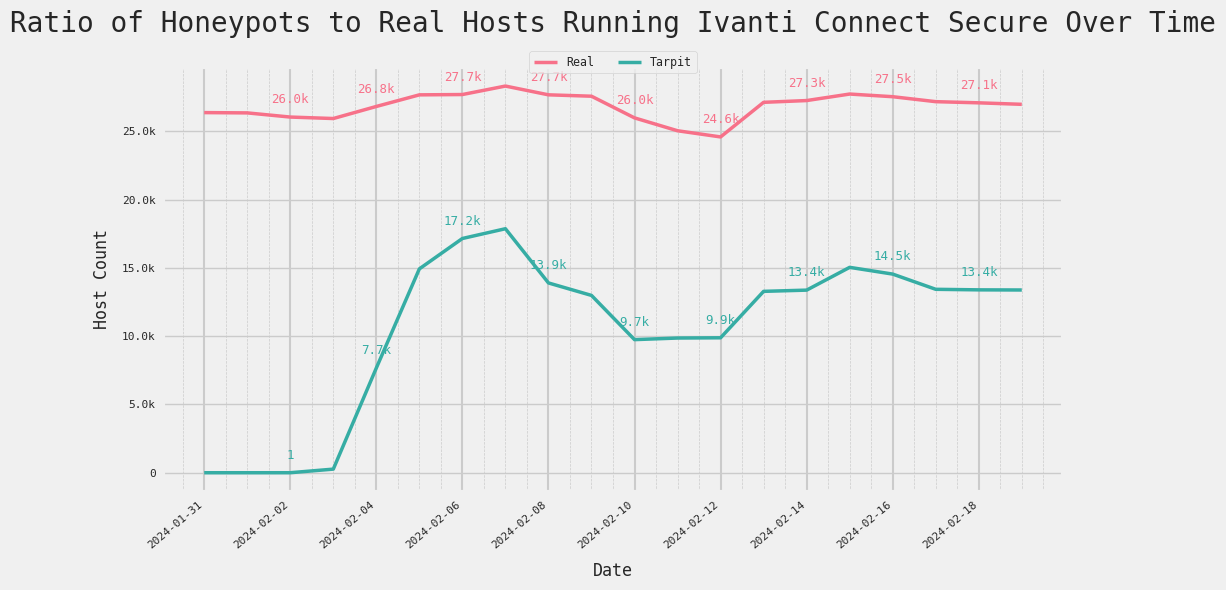

The graph above shows that the number of exposed hosts and services with Ivanti Connect Secure had a consistent line which hovered around 26,000 hosts and 27,300 services up until January 31, coinciding with when CISA issued an update to their original Emergency Directive.

However, when we checked those numbers again a week later, they shot up to ~41,800 hosts and ~46,000 services, basically doubling the host and service count.

Something unusual is going on here. This unexpected spike raises suspicions, as it deviates from the typical behavior of legitimate hosts. While the Internet is often slow to patch, it usually doesn’t spin up more affected hosts after a big zero-day vulnerability is announced.

When we took a closer look, the cause of this anomaly became apparent: honeypots.

In security and networking, a honeypot is typically a system or service strategically designed to mimic real targets. They do this to lure threat actors in to interact with the service so that their activities can be monitored.

At Censys, we’ve noticed a specific class of honeypot-like deceptive entities that seem designed to catch Internet scanners, as previously discussed in our blog about Red Herrings and Honeypots. These services attempt to emulate many different and legitimate software products over one service, making validation more difficult by flooding datasets with false positives.

The number of new Ivanti Connect Secure hosts was our first clue that something was amiss. Almost overnight, the total number of Connect Secure hosts doubled, which is an abnormal pattern for a single piece of software.

The difference between host and service counts was our second clue that these were likely honeypots. While the host count and service count were close at the beginning of the timeframe, the service counts increased disproportionately to the host count over the next few days, indicating hosts are creating multiple services, each reported as running Ivanti Connect Secure. On your average deployment of Connect Secure, only one or two services will show up as running this software.

Another more damning clue was the domain names that were found in each service’s Common Name (CN) section of their TLS certificates. Every single domain name looked out of place and, in some cases, too good to be true; that is, if the domains were real, they would be high-value targets such as production servers on government top-level domains.

Using a combination of the last two key indicators above, we were able to develop some simple logic that could classify these hosts as deceptive. The exact nature of this method will be explained later in this post.

Censys’s Perspective on Actual Ivanti Connect Secure servers

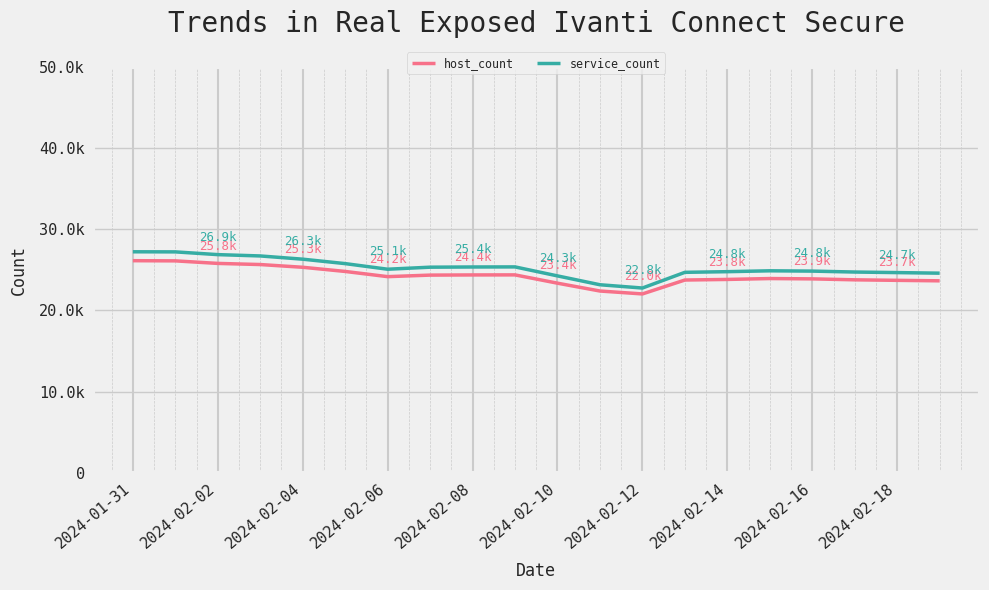

Excluding deceptive services, the trend aligns more closely with what we’d expect, showing a gradual decline in hosts and services as organizations begin to deactivate instances. As of Monday, February 19, 2024 Censys observed 24,590 exposed gateways.

Map of Exposed Ivanti Connect Secure Gateways on February 19, 2024 (Not all of these are necessarily vulnerable)

How many of these are potentially vulnerable?

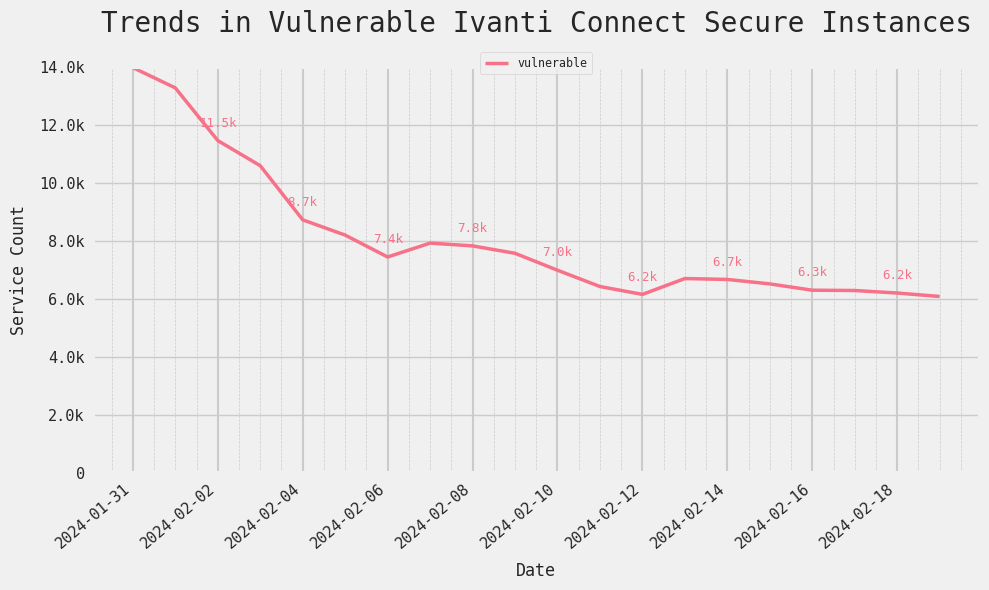

The graph below focuses on instances that show indications of running a version potentially vulnerable to any of the 5 recently disclosed vulnerabilities in Ivanti Connect Secure (CVE-2023-46805, CVE-2024-21887, CVE-2024-21888, CVE-2024-21893, and CVE-2024-22024).

On Monday, February 19, Censys observed 6,000 potentially vulnerable Ivanti Connect Secure gateways. It’s encouraging that that number has decreased by 56.5% from the 13,970 potentially vulnerable instances observed on January 31.

The trends in the figure above also correspond with the timing of CISA’s announcements – notice the sharp decline following the first update to the original Executive Directive (ED) released on January 31. There’s a relative plateau and small jump until February 9, the day CISA released their second update and provided “disconnect everything” guidance, after which the number of vulnerable services started decreasing again.

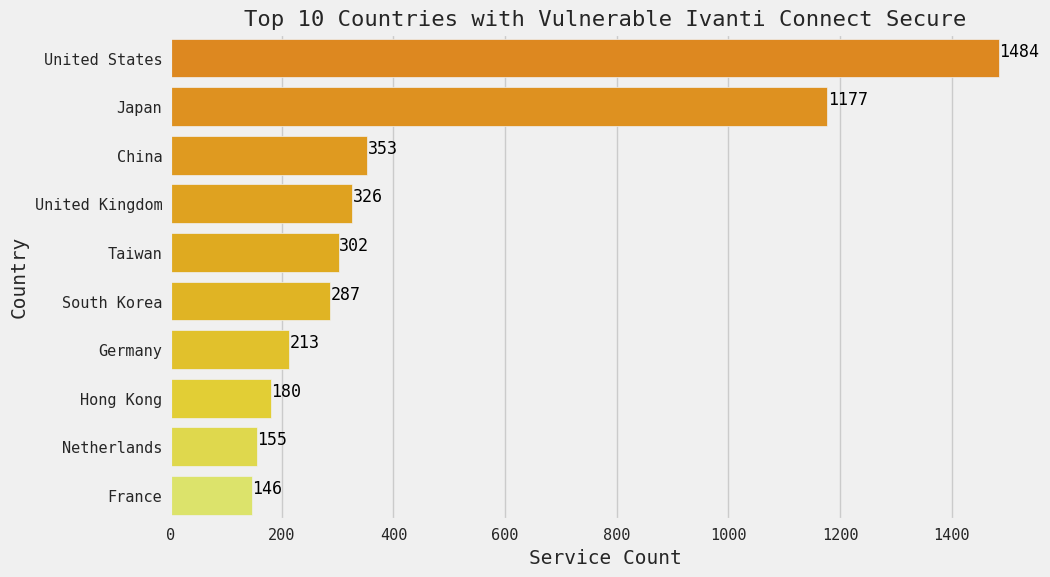

As of February 19, the concentration of these vulnerable gateways is notably high in the United States and Japan:

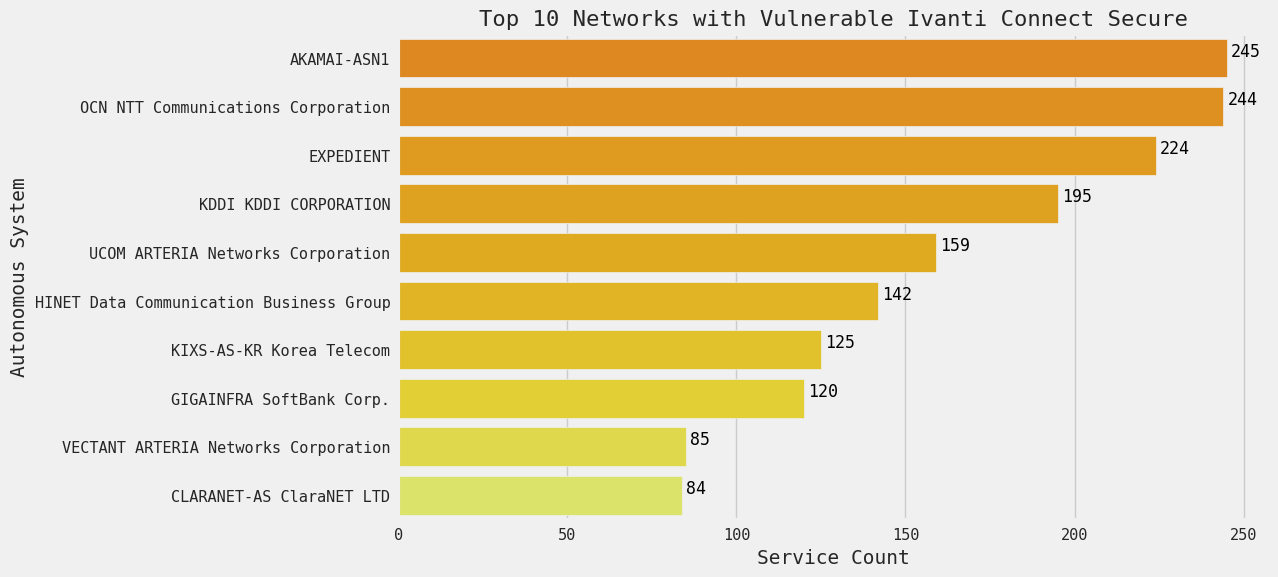

Many are running in a mix of major Japanese telecom and ISP networks. Most of the U.S. presence of these hosts is concentrated in Akamai as well as Expedient, a cloud services provider. NTT Communications, KDDI, and Arteria Networks are all major Japanese telecom and networking companies.

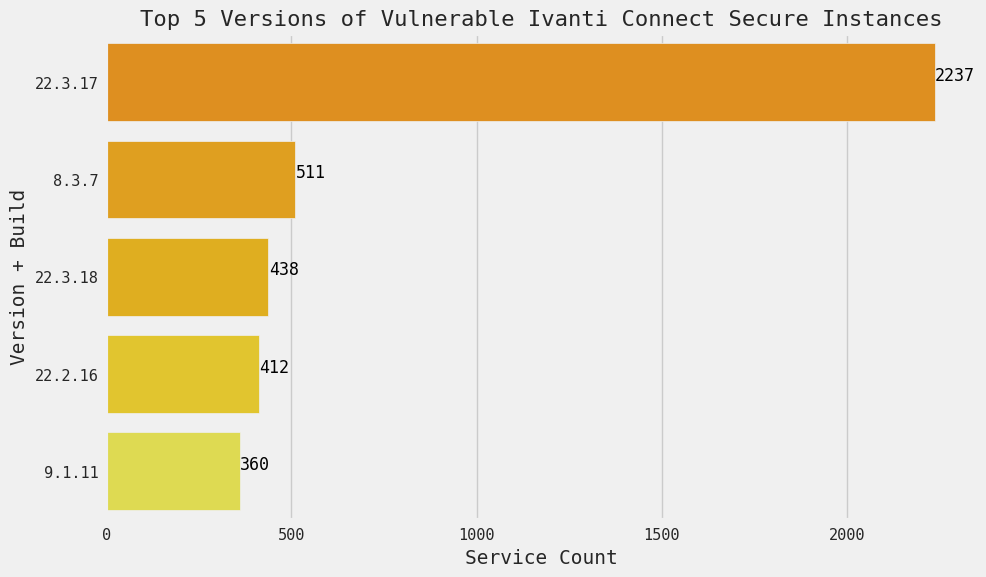

The most common vulnerable Ivanti Connect Secure version observed by Censys at the time of writing is 22.3.17. It’s concerning that the End-of-Life (EOL) version 8.3.7 ranks as the second most popular. This suggests that these instances may be legacy hosts that have been neglected or abandoned.

Digging into Deceptive Hosts

Now that we understand the real hosts that are exposed and running potentially vulnerable Ivanti Connect Secure instances let’s revisit the honeypots.

Initially, these hosts were tagged as Ivanti Connect Secure hosts in Censys, given their HTTP response bodies contained all the tell-tale signs of a legitimate Ivanti Connect Secure service. In other words, only after close inspection do we find that this was all a deception.

Above, we see that on February 2nd, the number of fake Ivanti Connect Secure services surged up to over 17,000 hosts, and this is one of the key indicators that clues us into the scale of this deception—a rare observation given that this surge happened around the same time as the vulnerability announcements.

Cutting Through the Noise

We used three primary indicators to determine what was legitimate and what was not.

- The number of unique hosts running Ivanti Connect Secure doubled overnight.

- There is a widening gap between the number of hosts and the number of Ivanti Connect Secure services (host count over service count).

- Suspicious common name elements in each service’s TLS certificate.

Since we’ve already discussed the surge in the number of installations and the widening gap between the number of hosts and services, let’s look deeper into the suspicious common names we found in the TLS certificates.

| dev.appliance.bright-manufacturing.mil |

| devo-hydro.state-medicine.ua |

| internal.thermal.first-finance.mil |

| pilot-vsphere.west-power.ua |

| private.sslvpn.city-oil.co.il |

| secret-kace.first-airforce.gov |

| staging.support.east-power.ca |

| pilot-sonicwall.south.oil.ca |

|

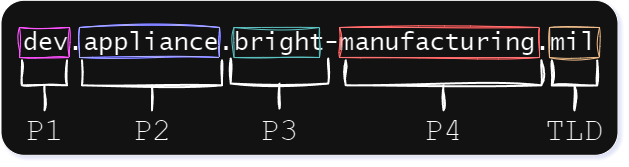

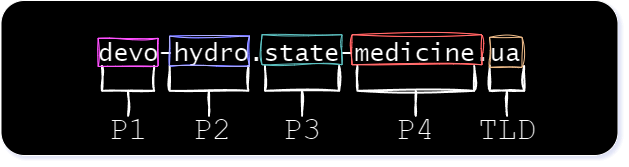

To the left, we see some examples of the common names found in these host’s TLS certificates.

To us, it seemed like these names were generated based on a predefined list of keywords. More specifically, keywords that were strategically chosen to be noteworthy for the sole purpose of attracting the eyes of an attacker.

For example, we found the presence of multiple government and federal top-level domains, such as “.gov” and “.mil,” along with prefixed tokens such as “private,” “dev,” or “prod” (denoting a private development or production system). All of which could be seen as a high-value target. |

Upon conducting a more comprehensive analysis of tens of thousands of these “unique” common names, a pattern emerged in the positional arrangement of these seemingly random domain names. First, we parsed each name into substrings and noted their relative position, for example, with pilot-vsphere.west-power.ua:

| Value |

Substring Position |

| pilot |

1 |

| vsphere |

2 |

| west |

3 |

| power |

4 |

| ua |

TLD |

We noted that each substring had a predefined set of potential values for its respective position in the string. You might observe that in the example list of certificate names provided above, the term “pilot” exclusively appears in the leftmost substring position (Position #1). This was true for “pilot” across all the common names we encountered.

Below are two diagrams showing the patterns we discovered and their respective token positions (“P1” through “P4” and the “TLD”). This means that a different set of words was used for each position to generate a fully qualified domain name. Whether a dot or a hyphen joined the tokens, the number of positions remained the same.

Below is a table where we broke out these sets to generate the top ten tokens used for each corresponding position and the number of times we observed each token at that position.

| Position 1 – #Occurences |

Position 2 – #Occurences |

Position 3 – #Occurences |

Position 4 – #Occurences |

TLD – #Occurences |

| preprod

37,804 |

helpdesk

13,923 |

bright

46,555 |

oil

40,150 |

ua

66699 |

| test

37,773 |

conveyor

13,896 |

west

46,389 |

power

40,137 |

mil

66617 |

| private

37,621 |

docs

13,785 |

next

46,048 |

aero

40,089 |

co.il

66610 |

| corp

37,587 |

exchange

13,727 |

City

46,047 |

bank

39,992 |

ca

66505 |

| beta

37,566 |

confluence

13,701 |

state

46,003 |

manufacturing

39,941 |

us

66470 |

| internal

37,548 |

accounts

13,696 |

today

45,948 |

steel

39,924 |

gc.ca

66,432 |

| development

37,349 |

support

13,692 |

novel

45,946 |

navy

39,898 |

com

66,220 |

| research

37,342 |

mfa

13,650 |

south

45,934 |

electric

39,839 |

org

65,941 |

| devo

37,319 |

jira

13,622 |

east

45,905 |

security

39,786 |

gov

65,522 |

| pilot

37,216 |

packaging

13,620 |

main

45,885 |

energy

39,747 |

N/A |

| AVERAGE: 37,512.5 |

AVERAGE: 13,731.2 |

AVERAGE: 46066.0 |

AVERAGE: 39,950.3 |

AVERAGE: 66335.1 |

As we can see, the unique words used in their respective positions have a fairly even distribution, which indicates a decent random number generator, giving further credence that there was a high degree of automation behind the creation and staging of these hosts. Below is a simple Python script that will mimic the base functionality of these (obviously) computer-generated domain names.

import random

import time

p1_toks = ["preprod", "test", "private" "etc..."]

p2_toks = ["helpdesk", "converyor", "docs", "etc..."]

p3_toks = ["bright", "west", "next", "etc..."]

p4_toks = ["oil", "power", "aero", "etc..."]

tld_toks = ["ua", "mil", "co.il", "etc..."]

random.seed(time.time())

p1_tok = p1_toks[int(random.random()) % len(p1_toks)]

p2_tok = p2_toks[int(random.random()) % len(p2_toks)]

p3_tok = p3_toks[int(random.random()) % len(p3_toks)]

p4_tok = p4_toks[int(random.random()) % len(p4_toks)]

tld_tok = tld_toks[int(random.random()) % len(tld_toks)]

print(f"{p1_tok}.{p2_tok}.{p3_tok}-{p4_tok}.{tld_tok}")

From One Comes Many

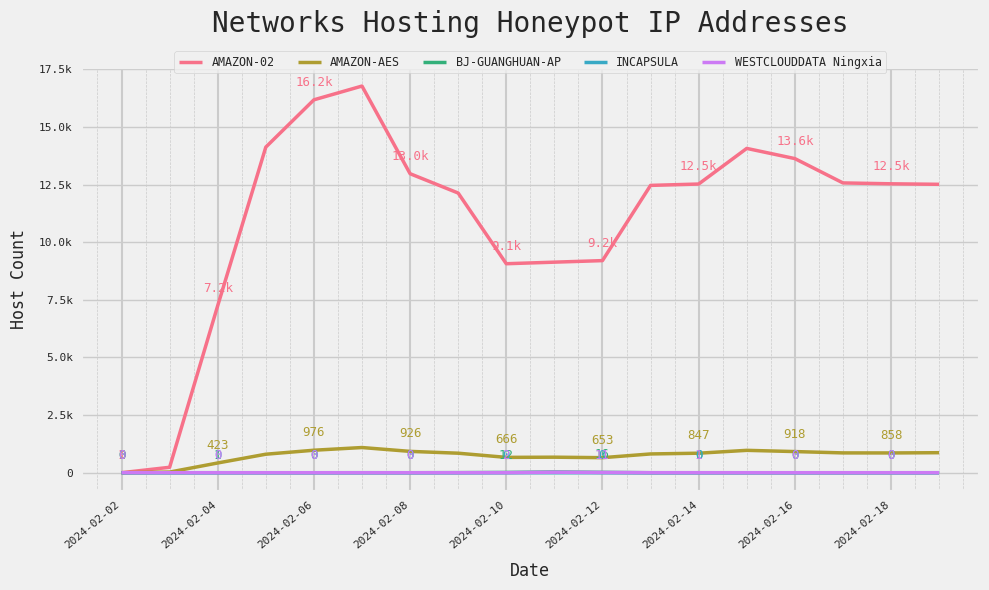

Censys first detected a solitary honeypot host running Ivanti Connect Secure on February 2. Within a day, the count surged to 260 hosts and rapidly peaked at around 17,900 hosts by February 7. The ability to deploy such a significant number of hosts in such a short time implies using considerable resources, indicating the involvement of a well-funded actor rather than an amateur.

Censys started actively labeling these hosts differently on February 15, after which they declined slightly in numbers but continue to persist.

Patient Zero

February 2nd, 2024, was the first time we witnessed a host with the fake Ivanti Connect Secure running with the characteristics described in the previous section (the randomly generated domain names).

| IP |

52.40.12.180 |

| Port |

2096 |

| Autonomous System |

AMAZON-02 (AS16509) |

| Country |

United States |

| Version |

Null (no body hash) |

| HTML Title |

Ivanti Connect Secure |

| Certificate Common Name |

staging.siemens.today-oil.ca |

There are a few interesting things of note about this service:

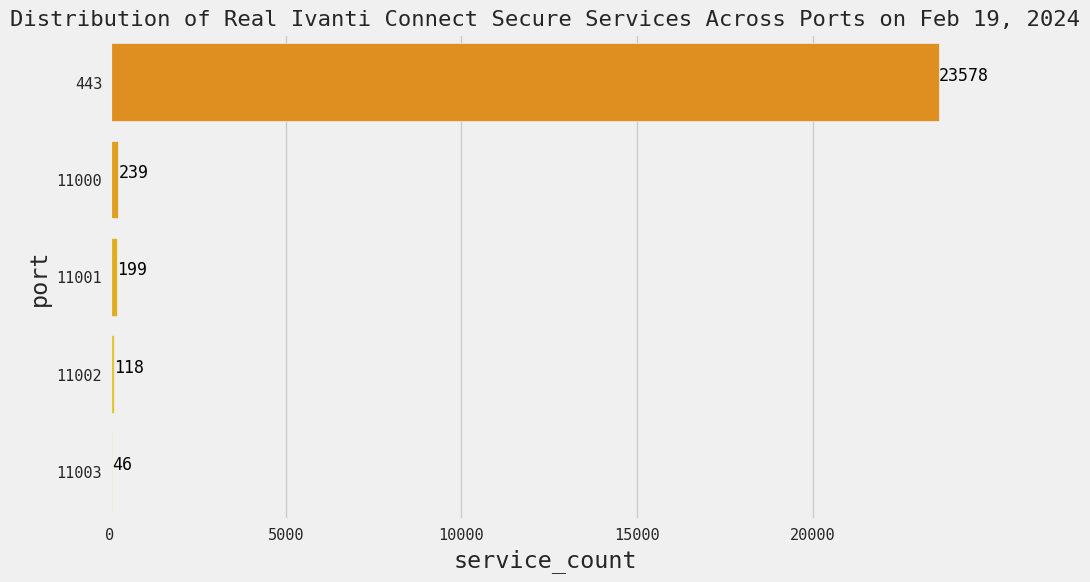

- It’s hosted on a seemingly random port that diverges from the normal behavior – the overwhelming majority of real Ivanti Connect Secure gateways are concentrated on port 443, as this graph shows:

- The host is in AMAZON-02, one of the most prominent AWS networks. This is also where honeypots were concentrated the last time we wrote about them.

- The certificate’s common name raises some suspicion. At first glance it looks like a legitimate cert, but when examined closely, the common name is an unusual combination of words for the root and subdomains.

Isolating the hosts that follow this certificate naming pattern, here’s how the distribution of honeypot hosts across networks changed over time:

Given that the majority of these services are hosted on AWS, identifying a specific owner poses a challenge. Nevertheless, a smaller subset of hosts were located in the autonomous systems `Ningxia West Cloud`, and `BJ-GUANGHUAN`, which serve as AWS’s transit providers in China. This alone hints at the involvement of an organization with connections to China since the account holder would be required to have an officially registered business license from China to spin up hosts in those specific AWS-adjacent autonomous systems.

There are a couple other pretty conspicuous signs that these are fake:

1. Mirror-image Host Count Trends Across ~10 Countries:

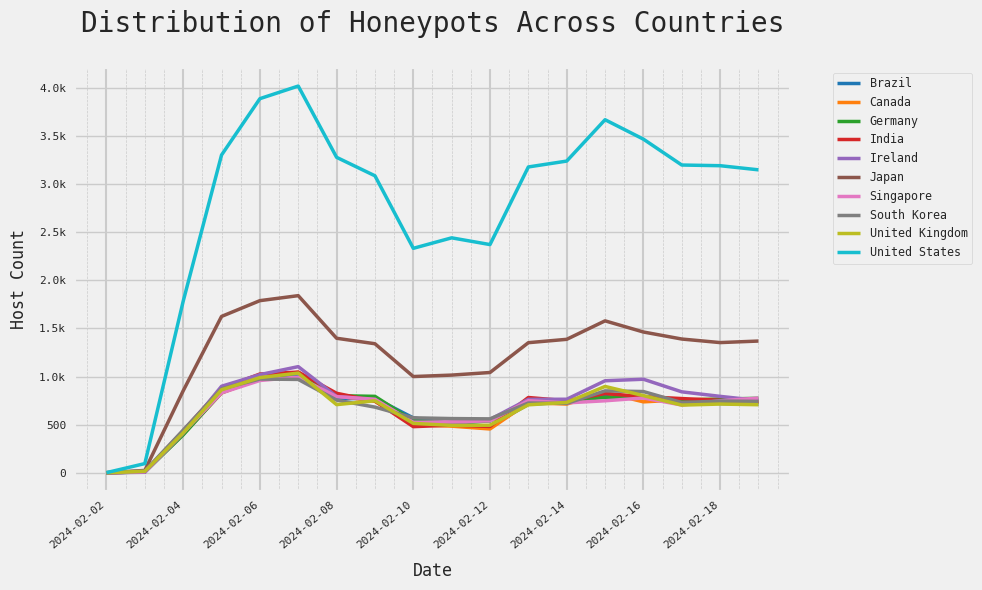

The figure below maps trends in the IP geolocation of these hosts:

Notice how there seem to be ~10 countries that all have remarkably similar host count trends here. This pattern suggests that these hosts were systematically deployed and monitored in each country, likely with the use of a script.

2. Uniform HTML Title, No Versions

All of them have the exact same HTML title: “Ivanti Connect Secure”, and no version could be extracted from any of them. Those shared characteristics reinforce our suspicion of “script-generated” behavior.

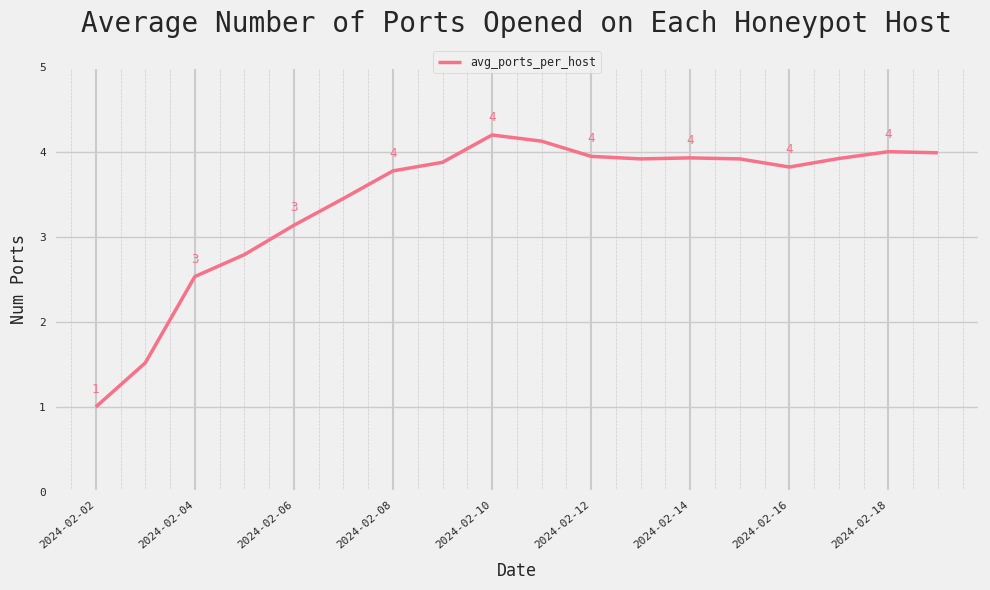

3. Rapid Increase in the Number of Ports per Host

Over time, the average number of ports on each host with Ivanti Connect Secure quadrupled from 1 to 4, as shown in the figure below. It’s unlikely that the average legitimate host would have the VPN gateway running on 4 separate ports simultaneously, or that they would increase RIGHT as major vulnerabilities are discovered.

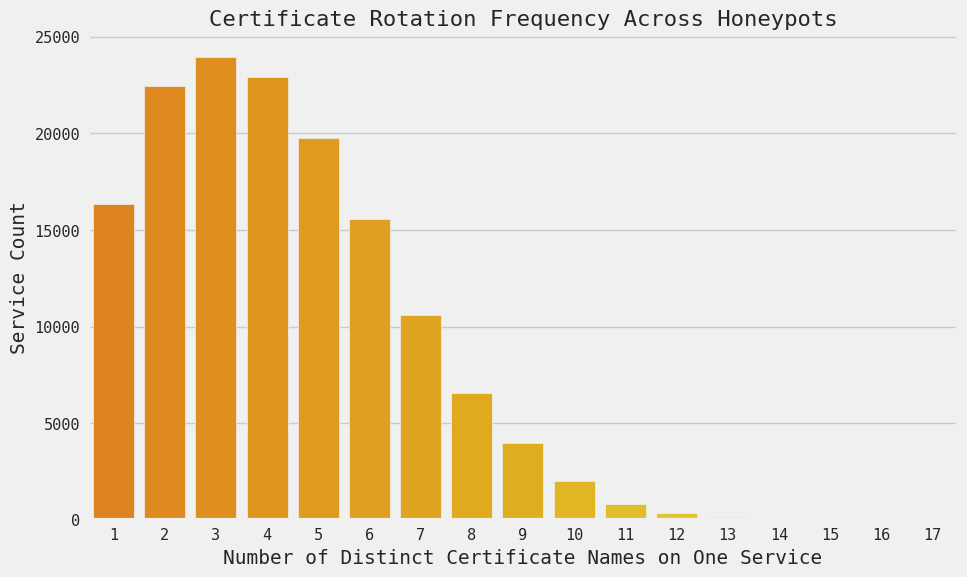

4. Frequent Certificate Rotation

We were interested in investigating whether these hosts regularly updated their certificates or altered their names. While the motivations for frequent certificate rotation vary, in the context of deceptive hosts one plausible hypothesis is that they’d do it to add a dynamic aspect that makes it trickier to distinguish between real and fake systems, possibly evading detection longer.

The graph below illustrates the distribution of the count of unique certificates observed on a single port throughout the entire analyzed time span (from January 31 to February 19).

| Distinct Common Name |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

| Number of Services |

16323 |

22465 |

23965 |

22935 |

19744 |

15552 |

10575 |

6547 |

3959 |

2007 |

797 |

347 |

152 |

42 |

25 |

8 |

6 |

Over the time frame of 20 days, Censys recorded a median of 4 unique certificates presented on a single port, with three specific services displaying as many as 17 different certificates. That rate of churn is not typical and suggests that something unusual is going on here. Again, in the absence of more definitive evidence, this is simply a hunch, but it does fall in line with our other observations.

This specific pattern of honeypot hosts is not exclusive to Ivanti Connect Secure. We’ve noticed similar hosts that appear to be running software related to other recent vulnerability announcements. Identifying who’s responsible is challenging at this stage, but the evidence is mounting that they’re doing it deliberately. We will keep an eye on the situation for further developments. 🔎

What Can Be Done? Remediation for Ivanti Connect Secure Vulnerabilities