On March 13, 2025, Juniper published an interesting article about a malware infection found on a set of Juniper MX routers that they were made aware of in July 2024. They have dubbed the campaign “RedPenguin.” This incident was fascinating because it looked incredibly advanced and required a deep understanding of Juniper routers’ operating system (JunOS).

Using compromised login credentials, these attackers installed several daemons that modify memory, establish communication channels for remote administration, clean up logs, and start up various IPC mechanisms.

What stood out immediately was the network communication methods. For example, the installed RAT called “jdosd” (Junos Denial of Service Daemon) communicates with a C2 server to execute commands and read and write files to the router. Utilizing a UDP listener on port 33512, it implements a fairly basic framing protocol that a network scanner couldn’t easily find.

Unlike TCP, where the server must send back either a SYN/ACK or SYN/RST, UDP is connectionless, which makes it challenging to scan as you have two options for determining whether a remote UDP socket is listening when the server does not initiate data transmission:

You can construct a packet that will elicit a response from the remote server. (e.g., sending a DNS query to port 53)

- Look for ICMP port unreach messages coming back from the remote server.

This is very unreliable due to standard filtering and host configuration.

So, with UDP, unless you can construct a packet where the server will respond with data, it’s nearly impossible to tell if something is on the other end. The UDP framing protocol for this “jdosd” process requires that a C2 server connects to it (a process reversed from most C2 operations where the compromised device connects back to the C2) and sends a specially crafted packet that includes some authentication information. Once this handshake has been completed, the “jdosd” process will start reading commands from the socket.

Unfortunately, as of drafting this blog, we could not obtain a sample to observe the connection handshake firsthand, so blindly scanning UDP/33512 for such a service was futile. Even if we could scan for it, we could only talk about who was compromised instead of who the attackers are, given that the attackers connect to the routers instead of vice versa.

But this is not the case for all of the malware that was installed; the services “/usr/sbin/appid” and “/usr/sbin/to” were identified to be a modified version of an open-source backdoor called Tiny SHell where several hard-coded IP addresses were found. The router will then connect to one of these IP addresses on port 22 and listen for commands to execute locally. These are the known hard-coded IP addresses:

- “/usr/sbin/appid”

129.126.109.50

116.88.34.184

223.25.78.136

45.77.39.28

- “/usr/sbin/to”

101.100.182.122

118.189.188.122

158.140.135.244

8.222.225.8

One thing to note here is that this was reported way back in July of last year, and we don’t even have an exact date for this report, just a generic range. This means that looking at the hosts as they currently are may not be the same as looking at them from that point in time.

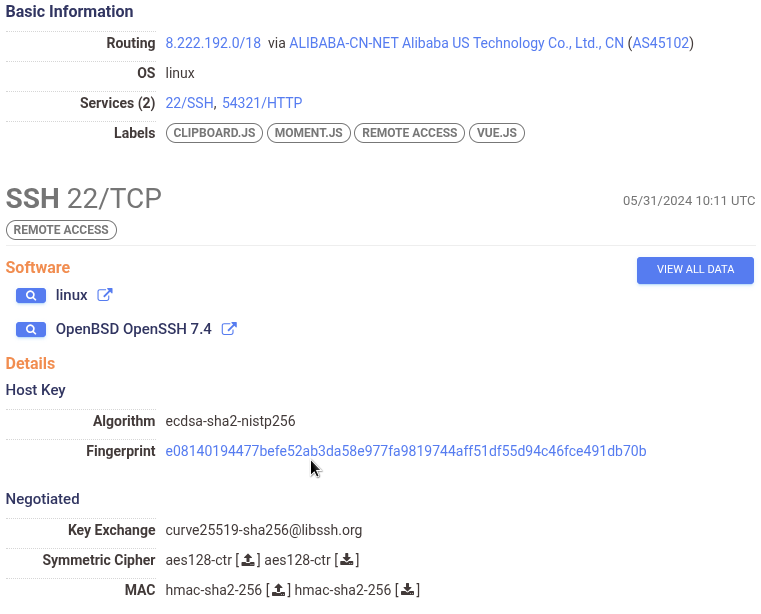

8.222.225.8 (above) consistently had only two services running between June 1st, 2024, and August 1st, 2024; the most notable is the service listening on port 22 (the port to which the TinySHell malware connects), which advertised itself as a standard everyday OpenSSH server. The existence of this specific service either means that this was not the port the malware originally connected to, or it’s a highly modified TinySHell server made to look like a real OpenSSH server.

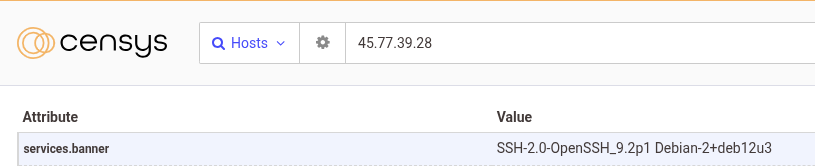

The only time 45.77.39.28 had any services running in this time range was at the end of July, specifically July 29th, 2024. Like the previous host, an OpenSSH server listened on port 22 and was removed two days later, on July 31st, 2024.

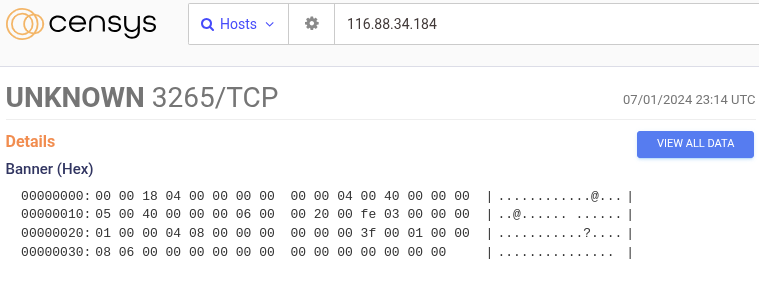

116.88.34.184 consistently had six different services running throughout July 2024, except for July 02, when a strange unknown service was started on port 3265 and stopped on July 04. Outside this anomaly, the host was a home media server running Plex, a Synology NAS, and an ASUS ZenWiFI AX Mini administration page (which may have been vulnerable to CVE-2024-3080). Like the prior two hosts, the service listening on port 22 was a legitimate SSH server running Dropbear instead of OpenSSH.

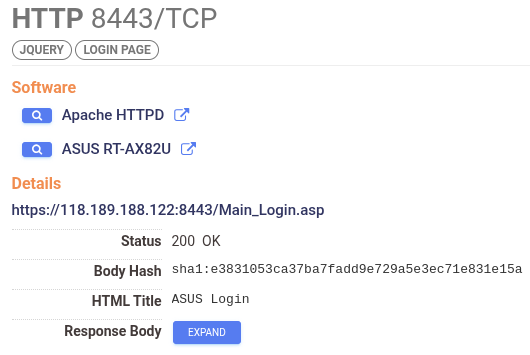

118.189.188.122 consistently ran only two services throughout July 2024: an ASUS RT-AX82U administration interface on port 8443 (which may have been vulnerable to CVE-2022-35401) and a Dropbear SSH server on port 22 (which are both still up and running as of March 13, 2025). Again, there is no sign of any unique service like TinySHell running over port 22.

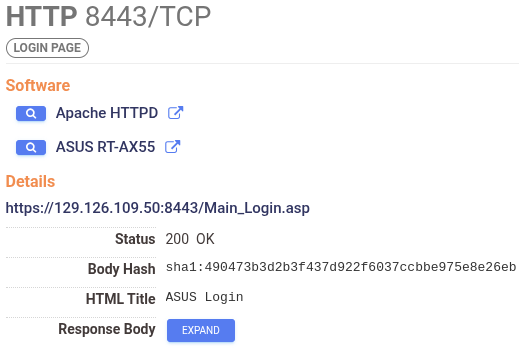

129.126.109.50 had two services running throughout July 2024: a Dropbear SSH service on port 22 and an ASUS RT-AX55 (which may have been vulnerable to an RCE reported by the Taiwanese CERT)

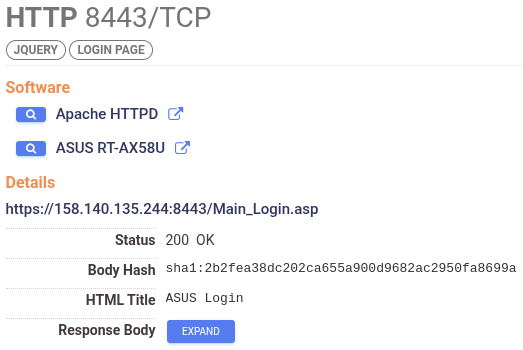

158.140.135.244 has been running the same number of services since July 2024. Port 22 is yet another OpenSSH server, and alongside a bunch of different ASP websites, we find yet another ASUS router (RT-AX58U) administration page on port 8443, which may have been vulnerable to an exploit we reported on back in June of 2024.

223.25.78.136, as it stands currently, is not the same physical host as it was back in July of 2024. Starting around July 07, 2024, we observed five different services: a Dropbear SSH server on port 22, an IKE VPN server on UDP 500, an OpenVPN service on port 1194, a serial to network (ser2net) service on port 5000, and yet another ASUS RT-AX58U router administration page on port 8443.

As for 101.100.182.122, we did not have any services running throughout July 2024, and we even looked a few months prior; it could be that our scanner somehow missed something.

We highlight these ASUS administration interfaces because if Mandiant is correct in assessing that these attacks were conducted via an ORB (Operational Relay Box) network, then many of the services you will see on the source hosts will look like residential SOHO-grade devices (such as ASUS routers). The reality is that these devices are (or were) most likely compromised and being used as proxies. And given that we know that ASUS has been a target of several large-scale hacking campaigns, it’s probably a safe bet to say that these devices were owned by innocent individuals but were controlled by malicious parties. It’s too strange of a coincidence that almost all of these C2 servers were running ASUS routers.