Using OSINT services for tracking malicious infrastructure

Introduction

Most cyber activity by malicious actors requires infrastructure like servers on the internet. The larger the campaign, the more servers are needed. Some APT groups used several thousand Command and Control (C2) servers over the years. For Threat Intelligence this offers unique opportunities for tracking such activities, because often the C2 servers need to be configured in a specific way and many actors have developed their idiosyncratic habits of setting up servers. An essential advantage over purely forensic investigations of incidents is that analyzing the infrastructure can sometimes identify C2 servers even before they were used in an attack. Internet search engines like Censys are crucial in this type of analysis. They collect information about hosts on the internet and their configurations, thereby saving researchers the effort of scanning large address spaces themselves.

This article explains why infrastructure tracking is possible, what attributes can be important to take a look on, shows two recent examples as well as an example process and gives some hints for starting out with infrastructure analysis. Keep in mind that this article only discusses passive methods for finding and clustering malicious infrastructure. Active methods, such as scanning for hosts yourself, introduces further possibilities such as mimicking a malware‘s handshake in order to identify C2 servers or victims with high confidence. Also, this article covers only HTTP(S) based infrastructure.

Background

There are multiple reasons why malicious infrastructure can be found via Censys and similar services, and most of them are due to mistakes in operations security (OPSEC). While the following paragraph is surely not exhaustive, it mentions a few key points why such mistakes happen. Some actors might not be aware of their mistakes, but others might even be aware of the impact on OPSEC. Yet, since they need to trade-off OPSEC for efficiency, they sometimes seem to decide to take the risk.

1. The pace of cyber attacks greatly increased While cyber attacks were the exception some years ago, today they are business as usual. Due to the growing number of targets, the demand of infrastructure also increased. In order to save valuable time, some kind of infrastructure automation is used to set up and configure servers. Some actors chose the easiest way by deploying prepared images, while others seem to set up C2 servers via some scripts.

2. Different teams are responsible for operating campaigns and setting up infrastructure While some experienced operators (who conduct the actual attacks) might know about OPSEC pitfalls, in some groups the infrastructure is set up by another team which is not aware of the technical possibilities to identify their servers.

3. Specific terms need to be used in order to appear legitimate to potential victims Often it is necessary to trick the victims into thinking the used infrastructure is legitimate. This can either be in order to hide in the general network traffic or because the victim would recognize suspicious addresses in the URL bar, e.g. for phishing campaigns.

4. No OPSEC-by-design In general, many actors do not seem to follow OPSEC-by-design. Instead of thinking beforehand how Threat Intelligence analysts could identify their servers, they seem to live by trial-and-error or at least only improve their OPSEC after being outed in a Threat Intelligence report1. Because we don’t want to provide OPSEC tips for recent threats, this blog post only covers already known infrastructure that has been blogged about.

Criteria for clustering hosts

There are multiple criteria that can be used for finding and clustering infrastructure. Some of them are listed here including the respective attributes which can be used for searching this host – as before, this list is not exhaustive. In general, there are three groups of criteria: response header, response content, and certificates. Because some threat actors use custom server-side software or specific library versions, responses to HTTP requests often include a characteristic combination of headers. So, hosts can be clustered either by the absence of a header or by specific header strings. We will cover an example for clustering hosts by response headers below. With Censys queries, headers can be filtered via

<port>.http(s).get.headers.

Also, the response content can contain characteristic artifacts. Some Command and Control servers try to mimic a specific web server and therefore deliver some kind of default page as index or error page. A well-known example is the use of the Microsoft Internet Information Service (IIS) default web page as an index page for Powershell Empire2. Scanning services typically access just the index page or receive an error page as a response if the C2 server expects a certain path to be accessed. In these cases, often the hash value of the response body can be used for clustering hosts.

Other actors sometimes use a default setup, where another website will be completely cloned first and changed afterwards. In these cases it can be helpful to search for specific resources in the website, such as used favicons, embedded javascript snippets (and ad network or tracking IDs that might be in there) or included css files. The last group of criteria are certificates. Filtering by serial number, fingerprint or distinguished name (see example 2 below) can be a useful way to cluster hosts by their certificates. Actors might tend to use a specific certificate authority along quite unique terms in the common name or even reuse self-signed certificates along all their infrastructure.

Both, response content and certificates, sometimes are created in a way that appear legitimate to potential victims and therefore include specific elements.

Example 1 – Tracking based on HTTP headers

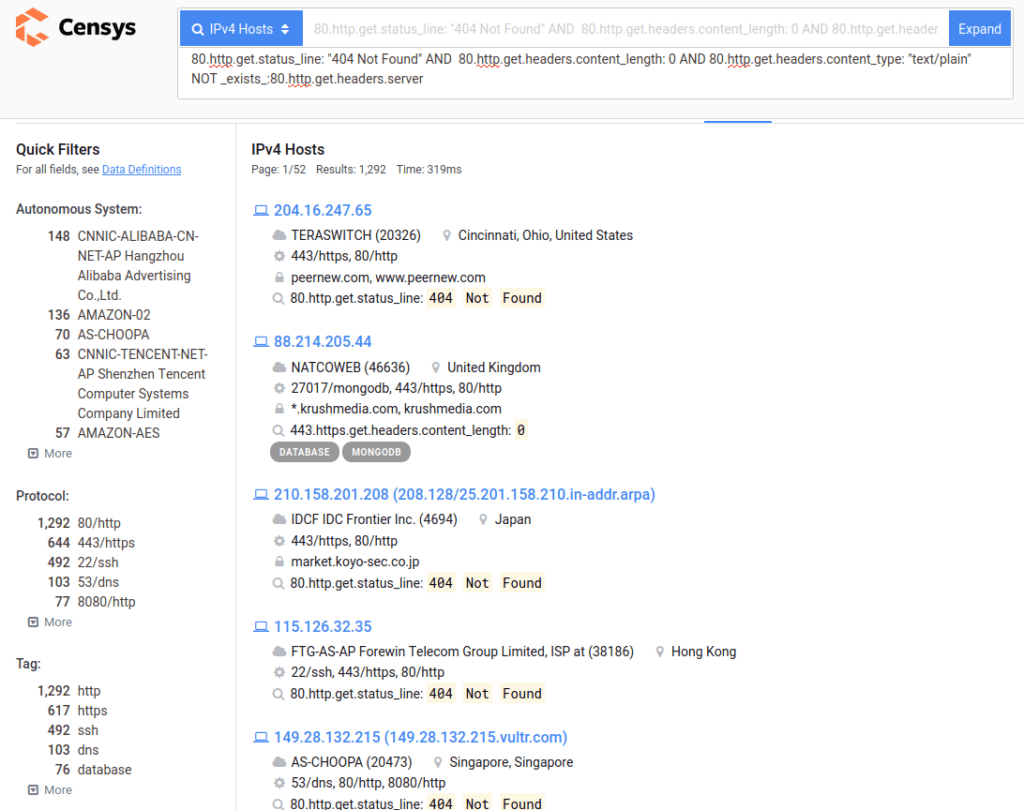

As a broadly known commercial penetration testing toolkit, Cobalt Strike (CS) is not only used by Red Teams. Over time, lots of different threat actors used (and probably continue to use) it as a first stage. The typical server response for Cobalt Strike can be characterized as follows:

- HTTP 404 Not Found

- Content-Type: text/plain

- Content-Length: 0

- Date Header

- No Server-Header

With these criteria, we are able to easily find servers using the following Censys query:

80.http.get.status_line: "404 Not Found" AND 80.http.get.headers.content_type: "text/plain" AND 80.http.get.headers.content_length: 0 NOT _exists_:80.http.get.headers.server

Censys query for Cobalt Strike instances on port 80

Be aware that not all results you see necessarily are Cobalt Strike instances, but it is a good indicator. Also, as you might have already guessed, Cobalt Strike is not limited to port 80. Apart from the default TLS certificate used by the tool, you can find other instances using TLS by additionally searching for popular certificate authorities or self-signed certificates.

87f2085c32b6a2cc709b365f55873e207a9caa10bffecf2fd16d3cf9d94d390c

Censys query using the SHA256 hash of the default Cobalt Strike certificate fingerprint

There is a tremendous amount of Cobalt Strike infrastructure available online, so you most likely need another type of data source, such as passive DNS data, in order to properly cluster the instances found.

Results for typical Cobalt Strike headers on port 80:

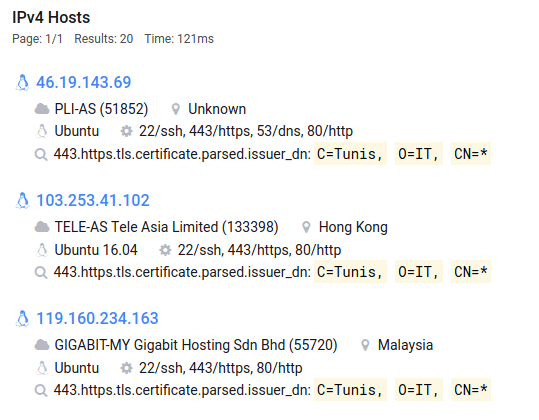

Example 2 – Tracking based on certificate data

In July 2020, NCSC UK, the national cyber security authority in the UK, published an advisory about APT29 targeting COVID-19 vaccine research3. The group also known as “The Dukes” or “Cozy Bear” used Citrix and VPN vulnerabilities to attack various companies connected to vaccine development. In these campaigns, the group used two custom malware families, WellMess and WellMail. The infrastructure used by the perpetrators included very specific self-signed certificates which made them easy to track, as reported by several sources. PwC recently published a report about the server side software used by the perpetrators4.

Issuer: C=Tunis, O=IT, CN=* Subject: C=Tunis, O=IT

By using the certificate distinguished names given in table 1, we can create a query in order to find recent infrastructure:

443.https.tls.certificate.parsed.subject_dn: "C=Tunis, O=IT" AND 443.https.tls.certificate.parsed.issuer_dn: "C=Tunis, O=IT, CN=*"

With the query in table 2, 20 hosts can be found using the certificate details.

Example Process

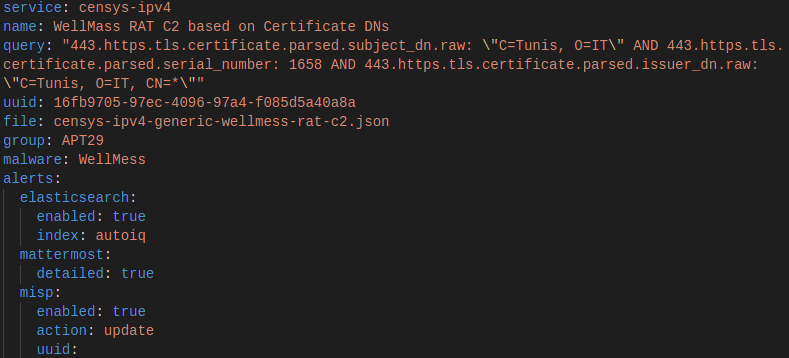

When I started with infrastructure tracking, I wrote a simple python tool that queried different data sources based on a given rule.

The rule (see figure 3) included the necessary query and the script sent the results to other systems. As those were purely used as notifications at the start, I called the section “alerts”. After setting up cronjobs to run your scripts, you’re good to go – without needing a huge software stack. In case I need the raw response from the queried sources, I store all API responses in a JSON file. This way I can create a completely new data structure if needed,

without losing data.

Tips for starters

While you’re going to develop your own procedures for infrastructure tracking, I want to give some advice for people starting out, hoping you find the following tips useful.

1. Combine different resources.

In order to get the most precise picture of the infrastructure used by adversaries, it is very helpful to combine various services that deliver different types of information. In addition to host data (e.g. from Censys or Shodan), pivoting through infrastructure can be enhanced through passive DNS data (e.g. RiskIQ or Domaintools) and certificate data (e.g. Censys or crt.sh). If you’re consuming data from different providers, you might want to use a common data model5.

2. Store results in a searchable and flexible way.

After you started with infrastructure tracking, you’re eventually going to have a lot of data in your hands and you definitely want to be able to search through that data very fast. Having your data in an elasticsearch cluster or a similar searchable data storage will save you a ton of time. When setting up your toolset, keep in mind that you might want to search through your data with regular expressions.

3. Keep older results.

Do not delete results of older search queries. Keeping and updating host information allows the discovery of interesting patterns. Also, it is quite useful to have first and last seen dates for C2 servers.

4. Document your queries.

Your ever-growing number of queries need to be documented somehow, otherwise, you’re going to lose the overview. A good starting point is to create a schema2 that includes metadata such as a description.

Conclusion

Threat actors are bound by similar constraints as network defenders – time, money, skills, and laziness. This leads to mistakes or certain habits when setting up their infrastructure. With some creativity and tooling network defenders can exploit those mistakes and habits to track malicious infrastructure. The reward will be IoCs and insights into the activities of the attackers. Censys and other tools give analysts a great head-start. The magic then is in the queries that you write. I hope you found the above techniques and tips helpful. I’ll be happy to hear about your experiences, you can reach me via Twitter6 or Keybase7.

- Compare p. 75 Steffens, Timo (2020). Attribution of Advanced Persistent Threats.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-61313-9 ↩ - Compare https://github.com/BCSECURITY/Empire/blob/master/lib/listeners/http.py#L262 ↩

- NCSC-UK (2020). APT29 targets COVID-19 vaccine development.

https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/files/Advisory-APT29-targets-COVID-19-vaccinedevelopment.pdf (accessed 2020-09-21) ↩ - PwC UK (2020). WellMess malware: analysis of its Command and Control (C2)

server. https://www.pwc.co.uk/issues/cyber-security-services/insights/wellmessanalysis-command-control.html (accessed 2020-09-21) ↩ - Common OSINT data model for infrastructure analysis:

https://github.com/3c7/common-osint-model (accessed 2020-09-21) ↩ - https://twitter.com/0x3c7 ↩

- https://keybase.io/nkuhnert↩